|

RELIGION

IN THE NEWS |

|

|

Quick Links:

From the Editor: |

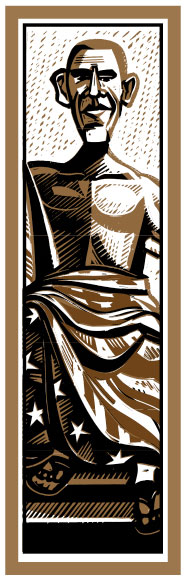

The Wright

Neighborhood For almost 12 years, I’ve been a member of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago. I’m also a professor of theology at the University of Chicago, an ordained American Baptist clergyperson, and an academic scholar of the black theology of liberation. I’d like to share some reflections on what it means to be a member of Trinity, on the type of Christianity it practices, and on its just retired pastor, the Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright, Jr. Traveling west to Trinity on 95th street, you have to cross the railroad tracks. Here, on Chicago’s deeply segregated south side, bleak trains carrying the freight of the city’s cross-country business can hold up worshipers for 15 minutes. It’s a neighborhood of empty lots and low-rent apartments, with here and there a small grocery store, a McDonald’s, a hair care shop. On the city’s north side, wealthy whites own $2-million lakeside homes and send their children to excellent public or elite private schools. Police officers ride bicycles and stop and have ice cream with the public. On the south side, the cops ride two to a car, wearing bulletproof vests and brandishing shotguns. Yet thousands of Christians from all over the Chicago area make their way to this place in order to attend Trinity. The 8,500 members and countless occasional seekers not only jam into the building for three regular services each Sunday, but also come for social services and spiritual healing every other day of the week as well. When you enter the church, you are met at the door by smiling greeters. “Welcome to Trinity,” they cheerfully exclaim. “This is the day that the Lord has made.” The ritual of “holy hugs” begins there at the threshold. Like Wright before him, the new young pastor, Otis Moss III, announces jokingly that if you don’t like a whole lot of hugging, you’ve come to the wrong church. The official greeters turn you over to a second group. With a warm smile, the latter hand you a church program, an envelope for your money, and possibly some educational literature—concerning what bills are being discussed in Congress, for example, or the latest anti-union activities of Wal-Mart. The second greeters invite you to follow an usher who will try to find you a seat of your choice. All the time, one of the church’s many gospel choirs is warming up the growing congregation before the official church service commences. Once seated, you notice people are singing, shouting, and dancing. I first heard of Trinity when I entered New York’s Union Theological Seminary in 1981. We young men and women training for the ordained ministry dreamed of what big churches we would preach at some day and Trinity was always in the top of our list. It was known as a unique place where a biblically based gathering of people took seriously the plight and the possibility of the working poor on earth. Its pastor had built an 87-member congregation into several thousands. It was probably the first church in the United States to place a “Free South Africa” sign on its lawn. On the seminary grapevine, if a young upstart could preach there, then he or she could deliver the Word of God anywhere in America. I first met Wright three years later, when I attended a national meeting of religious leaders as a student representative. He fit in easily among the giants of pulpit and professoriate. He was also humble and unassuming. He told the funniest jokes and made you feel like you were just hanging out with friends. But when he spoke to serious issues, he displayed a remarkable grasp of the Bible—in the original Hebrew and Greek (to say nothing of his command of six other foreign languages). I later found out that he had several graduate degrees, including one from the University of Chicago Divinity School. He was clearly a busy guy. During formal sessions of the gathering, he answered stacks of letters (this was before the BlackBerry age) even as he participated in the deliberations. But he wasn’t too busy to talk to me, a young student. In 1992, four years after starting my teaching career at Santa Clara University in northern California, I received a call from a staff member at Trinity who said Rev. Wright wanted me to come to Chicago and preach at his church. He had been reading my publications and asked that I share a word on the subject of my third book, which dealt with black theology in the slave narratives. I arrived at the original Trinity church that year and gave a sermon that was more classroom lecture than the “hooping and tuning” style of classic black preaching. But I felt like a real preacher: A driver picked me up at the airport, I stayed in a hotel, food was constantly served to me while at the church, and I received my first honorarium. If I had known then who regularly circulated through Trinity’s pulpit, I don’t know if I would have accepted the invitation. Pretty much all the major black pastors (including such international celebrities as Allan Boesak and Desmond Tutu of South Africa) had preached there, and when they did, they brought their “A” game. Preachers do not make a practice of surrendering their pulpits to unknown quantities like me. Wright, I discovered, was an exception. He constantly took the risk on new energy. When Wright came to Trinity as a young preacher, he changed the reading of the Bible and introduced gospel music and sacred dance. The word spread on the south side of Chicago, and the youth and young adults began to flood the church. But he always combined tradition with innovation, the solidity of seniors with the brashness of youth. In later years, the man came to embody the method. His outside reflected the gray-haired wisdom of an elder, while the inside harbored a youthful trickster figure eager for spontaneity. The world witnessed both sides during his now famous appearance at the National Press Club April 28. The first part showed a senior pastor reading from a prepared text—one divided into learned comments on liberation, transformation, and reconciliation. In the question-and-answer session that followed, the quick-witted trickster tradition of black preachers took over. Another story points to Wright’s appreciation of youthful brashness. Once, after giving a lecture at a seminary, he was asked by the black student preachers for a more intimate meeting. A bold, talkative group aggressively entered into the theological and homiletical nuances. After entertaining their queries, Wright asked them about their studies and their finances. They admitted that they didn’t have enough money to buy the books they needed. Wright pledged to pay for the books if they kept their grades up. The students were amazed. They had come to take on the big-time preacher and instead learned a lesson about the importance of focusing on their lessons. Black church ministry, he made clear, required high academic training. Wright led by surrendering leadership to ministries (or committees) that combined those who had made it in the outside world with those who had never known worldly success. He made such mixing the norm. The annual 10-week Bible study classes I teach at Trinity include unemployed poor people and downtown businessmen, city bus drivers and JD-MBAs. At the center of Wright’s ministry has been service to the least of those in American society and the world. Trinity’s 80 or so ministries include drug rehabilitation; prison work; various forms of outreach to children and adolescents; HIV and AIDS; cancer; outreach to Africa and the Caribbean; many different choirs; food and clothing banks; housing for seniors and low income communities; provision of Thanksgiving and Christmas food and toys for youth in surrounding public housing; formal academic classes for those preparing for the ministry; scholarships for seminary students; the largest black college fair in the city of Chicago; domestic violence groups; men’s and women’s prayer groups; employment counseling; legal aid; free medical networking and services; math and science tutoring; and individual prayer teams. Wright inherited his commitment to service from his father, the Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright, Sr., who was one of the most important black preachers in Philadelphia with strong connections to progressive national movements in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s generation. Wright, Jr. grew up meeting preacher men of service from around the country who visited his father’s church and home. His mother and father had both earned doctorates. His was a household that stressed affirmation of the educated black self in service to the larger community. Nor was it only a black thing. When Wright heard President Kennedy tell Americans to ask what we can do for our country, he gave up his student deferment and joined the Marines. After serving honorably and receiving an honorable discharge, he enlisted in the Navy and became a certified medical technician, at one point serving on the medical team for one of President Johnson’s operations. At Trinity, Wright made sure that service was international, eventually leading groups of parishioners on semi-annual educational trips to Africa and the Caribbean. I remember visiting an impoverished township outside Cape Town on one such trip. The Trinity bus unloaded several dozen members who then entered an old broken down church building. The South Africans sang and sang and prayed for their “brothers and sisters” visiting from across the waters. When I looked around, I could see parts of the roof had holes in it and pigeons nesting in the ceiling. It turned out that the pastor of the church had lost the job he had opening up a local business in the morning. One day, two white police officers had shot him six times, assuming that he was a robber who just happened to have the key to the establishment. Wright listened to this story and pledged to pay the pastor’s salary from then on. This is the Jeremiah A. Wright, Jr. that the membership of Trinity U.C.C. knows. It’s why the March 17 YouTube clips, looped by the media throughout the world, seemed like an alien imposition, a ripping of our pastor out of his context. It was Trinity itself that adopted the slogan, “unashamedly black and unapologetically Christian,” before it hired Wright. Wright was hired to put the slogan into action. The idea was to prepare its members to serve the larger American extended family by affirming the positive dimensions and criticizing the negative aspects of being black, by learning from traditions about Africa (and America), by seeing strong black men, boys, and fathers taking responsibility for their families and communities, and by witnessing the ordination of women and their leadership roles. I joined Trinity because of the spiritual safety of its own extended family. I joined because they preached and practiced a black theology of liberation—because Wright combined a deep reading of the Bible, a highly educated leadership, evangelical worship services, dozens of ministries for poor communities, strong labor advocacy, ordination of women, a welcoming of gays and lesbians, outreach to Africa and the Third World, and a quick wit and humor in one diverse community. These intimate and at times contentious inner-city Southsiders are primed for in-depth educated exposition of the Bible. They yearn for institutions of service to the left-out communities. They relish the opportunity to create new ways of building a devastated physical area. And they enjoy the occasional cutting sermon that speaks truth to power and calls out the names of those who have done wrong in contradiction to their interpretation of the Bible. If they had not wanted what Jeremiah Wright had to offer, they would have fired him and gotten another leader. About 13 years ago, Wright wanted to turn the church over to a younger generation so he could move on to finish up his book projects and do some seminary teaching in the Caribbean. The church refused to let him go. So the compromise was that he would stay until building projects had been completed. A retirement date was fixed for the beginning of 2008. Now Senator Obama has chosen to formally leave Trinity United Church of Christ. The corporate media hype around him running for president and the intense media scrutiny, bomb threats, and, in some cases, harassment and death threats against churchgoers became distractions for Obama and the church. The recent controversial comments of the well-known Chicago priest, Father Michael Pfleger, from Trinity’s pulpit, appear to have been the last straw for Obama. Though the senator praised the church for its continued good works, he decided that his family would find another religious home. We could argue for a distinction between Rev. Pfleger’s opinion and Rev. Wright’s sermon. Pfleger crossed the line because he impugned the humanity and personhood of Senator Hillary Clinton. Using the customary style of black preaching as a ritual of theatrical performance, Wright offered his versions of public policy and historical race relations. When Wright talked about “chickens coming home to roost” after the 9/11 attacks, he was quoting and paraphrasing the former U.S. ambassador to Iraq, Edward Peck. Peck, a former White House anti-terrorism official, had expressed those very sentiments about September 11 four days after the attacks and the day before Wright delivered his sermon. Peck is a white man. When Wright briefly mentioned “God damn America,” he was following the example of the Hebrew prophets. Yahweh/God made a covenant with ancient Israel in which Israel was given resources and abundance in return for following the divine commandments. When Israel strayed from the covenant, Yahweh/God raised up prophets to pronounce divine judgment and religious condemnation—damnation—on a wayward nation. That is why, in the 10-second sound bite, we see Wright say, “I’m in the Bible.” Now that Obama has left Trinity, a question remains. Will the nation be able to use the media firestorm over Trinity and the black church to pursue the healing conversation on race, faith, and politics that Obama called for in his “A More Perfect Union” speech in Philadelphia? Or will it only serve as a club for his political opponents to beat him with? |